|

Ola and Per |

|

There are two older fellows,

Whom I hold very dear;

The name of one is Ola,

And the other one is Per.

But whether they are real,

I certainly can't say,

I see them just as fantasy,

A dream by night or day.

The roles they play

In our Western Home out here

Are meant to ease and lighten

The burden that you bear.

For most of us can see

That when everything goes wrong,

A little fun and foolishness

Make it easier to get along.

|

There are some folks among us

Who think that it is bad

For us to laugh and joke,

Instead of looking sad;

But let them live their own way

In sad and solemn tune,

And then let them crawl back

Into their, own cocoon.

But we are glad to know

That living here and there

Are little boys or girls

Just waiting for our Per,

And for our Ola, too,

Without a cap, but snug,

Plus poor old Doctor Lars

With his musty, ancient jug.

|

|

Original printed in Decorah-Posten,

January 8, 1926, p. 5)

Peter Julius Rosendahl

(tr. E. Haugen |

In the Upper Midwest humor lives

among the descendants of Norwegian-American immigrants mainly in

the tall tales spun by the coffee gang gathered in the

small-town corner cafes, in the numbskull riddles and jokes

passed on by the teenagers, and in the comic strip Han Ola og

han Per. Drawn by Peter Julius Rosendahl from 1918 to 1935

for the Decorah-Posten, a Norwegian language newspaper,

the comic strip was reprinted almost continually until the paper

ceased publication in 1972.

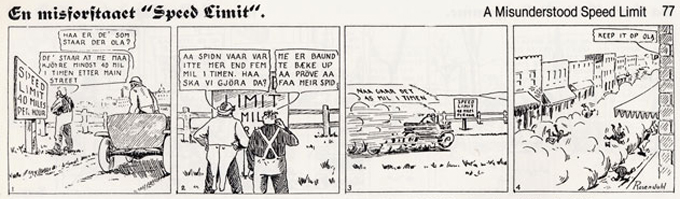

[1] This comic strip created by a Spring Grove, Minnesota,

farmer was one of the Decorah-Posten's most popular

features.

[2]

Han Ola og han Per was also unique in the three

major Norwegian-American newspapers which led a flourishing

immigrant press from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth

century.

[3] By 1918 when the comic strip first appeared, the

Norwegian-American immigrants constituted an ethnic group,

numbering nearly two million, with established traditions and

culture predominantly rural. An important recorder of the

culture, the newspaper used the comic strip to build and

maintain circulation among the Norwegian immigrants. During the

1920's the Decorah-Posten reached its top circulation of

about 45,000 subscribers, most of whom were midwestern

Norwegian-American immigrants and their descendants, but by 1950

the subscribers dropped to about 35,000.

[4]

That the Spring Grove, Minnesota,

farmer-artist was familiar with the Norwegian-American immigrant

culture is evident from his biography as well as from the

language and contents of the comic strip. Rosendahl's parents

were Paul and Gunhild Rosendahl, early Minnesota pioneers who

homesteaded during the early 1850's on a farm southwest of

Spring Grove, Minnesota, the oldest settlement of Norwegians in

Minnesota. The father, Paul, who emigrated from Hadeland,

Norway, distinguished himself by his Civil War service, by being

a Register of Deeds for Houston County, and later by being

elected to the Minnesota State Legislature. Similarly, Peter

Julius engaged in a variety of occupations besides that of

cartoonist. Born in 1878, he lived his entire life in his home

community, where he attended the public grade school. This rural

community in southeastern Minnesota, almost on the Iowa border,

was the scene he portrayed in his comic strip. His only formal

training in art was a correspondence course from the Federal

School of Applied Cartooning at Minneapolis during the years

1919-1920. Not only a farmer and a cartoonist, he wrote poetry

and song texts, painted portraits, and made sketches and

drawings. He drew many single cartoon-like pictures of

personalities, inventions, and objects in addition to his weekly

comic strip. A quiet, modest man, he married a second-generation

Halling, Otelia Melbraaten, and they were the parents of four

children. Rosendahl was not widely traveled, but he revealed his

vivid imagination in the ludicrous situations in which he placed

his protagonists and in the wild adventures which they survived.

During the summer and fall when he was busy with farming,

Rosendahl often had his comic strip characters bid the readers

"good-bye" until fall. Frequently the readers then wrote letters

to the editor to request that Han Ola og han Per return.

After 1935 Rosendahl could not be persuaded to continue the

comic strip. In 1942 he took his own life.

[5]

Today

Han Ola og han Per is

significant because it illustrates the traditional primary

values of humor: as entertainment, for anyone able to read

"Spring Grove Norwegian", which is discussed in Einar Haugen's

essay on the language; as literary and graphic artistry; and as

history, with predominant folklore elements, which reflects

mainly an immigrant society's pains and difficulties of adapting

to mainstream America with its rapidly changing customs and

attitudes. The artist described the roles played by Ola and Per

in helping to lighten the burden in their "Western Home." He

claimed:

When everything goes wrong,

A little fun and foolishness

Make it easier to get along.

[6]

He explained that people who

thought it ridiculous to smile should be permitted to live in

their own serious way, but he preferred to know those who

eagerly awaited the weekly appearance of Per, Ola, and Dr. Lars

with his old musty jug.

Rosendahl's comic characters made

their first appearance on Tuesday, February 19, 1918, in the Decorah-Posten, and during that year five more comic strips

appeared. These were representative in introducing the main

farmer protagonists, Ola and Per, who had endless problems in

coping with mainstream American life, and in exploring

Norwegian-American vernacular. The first strip, ten scenes with

captions along the bottom in addition to the dialogue given in

the balloons, describes Ola's ride in his new car and the

ineptness of his friend, Per, in helping him tame his

"cyclone-pet," or in "Spring Grove Norwegian," "Karsen" [the

car]. This strip sets the predominant plot pattern of the

characters making an attempt to improve their lives, only to

have their efforts end in disaster. The slapstick of the old

Keystone comedy formula of pies in the face, punches on the

nose, and falls in the mud characterized the series from the

beginning.

The second strip, printed in seven

vertical scenes on April 16, 1918, depicts the good neighbors'

attempt to capture a skunk by following the instructions given

in an English book which they had to interpret in Norwegian. Of

course, something went wrong, and Ola hit Per instead of the

skunk. This second strip also reveals that the series was used

to solicit readers for the Decorah-Posten, for where else

had the characters read that that newspaper offered five dollars

for one skunk skin? Ola and Per decide to complain to the

newspaper about the kind of fool who prints such misleading

information. This second strip also sums up the philosophy of

the series in the biblical saying that "the last will be worse

than the first."

The third strip, three vertical

scenes, published April 26, 1918, describes kind-hearted Ola's

hypocritical sadness at Per's mistreatment of the pigs and the

cow's contentment with Ola's fine care. This contrast of the

highfalutin person who cannot carry out simple tasks with the

common man who shows sensitivity in caring for creatures, and

furthermore even with the animals that talk and express

emotions, is basic to the series and well rooted in the native

American humor tradition.

The last three strips of the first

year continue these features while the artist was experimenting

with format and developing the characters and situations. The

fourth comic strip, which was nine scenes in length (Decorah-Posten, 28 May 1918), mocks Per's pretensions to

success as a lover. Foiled by the girl's parents when he

attempts to sneak into her bedroom by crawling up a ladder, Per

at first blames the unpredictability of women as the cause of

his misfortune but in the last frame, he wisely admits he had

only himself to blame. This strip, incidentally, alludes to a

well-known rural Norwegian custom known in New England as

bundling.

The fifth strip, three large

vertical scenes (2 August 1918), makes fun of the protagonists'

inability to put a ring in the nose of the huge hog that Per

owns. The beast bests them both and gives Per quite a ride on

the hog's back while Ola hangs on to the hog's tail for dear

life. Throughout the series animals outwit humans frequently,

thereby suggesting the superiority of the animal to the human

world.

The last strip of the year, a

"drama in four acts" (13 December 1918), shows Ola being whacked

by Per when he tries one of Per's inventions for slaughtering

the hog that, of course, goes free. All these comic strips

expose the world as being other than what it seemed to be. The

implication is that since the universe was believed to be

orderly or purposeful and man a rational creature, deviations

from these standards were ridiculous. In this last strip the

format changed; the captions disappeared and the four panels

were published horizontally in double-decker fashion at the

bottom of the page.

When the comic strips resumed

publication in the Decorah-Posten on January 9, 1920,

after the appearance of only one strip in 1919, the title, Han Ola og han Per, was used for the first time. But the

next five strips returned to the vertical format. With the

placement of the entire comic strip horizontally on April 30,

1920, the customary format of four panels across the bottom of

the page, usually on page three in the Friday edition of the

paper, began. The standard size and length of the comic strips

were retained throughout the publication of the strips until

they ceased their original run on July 19, 1935.

The "Ola and Per" series came into

being slowly, and during the first four or five years it did not

have the continuity it later developed. Usually during each

year, too, the readers could count on Ola and Per's taking a

vacation. This event was announced by a special ad in the Posten, and their return was heralded by sneak previews

weeks in advance so that new subscribers could catch their first

re-appearance. When Per and Ola returned to the newspaper, they

always came back home to the vicinity of Decorah, Iowa, since

most of the subscribers were familiar with the "home town." The

only drawing of this city nestled among the hills seems to be

authentic.

Rosendahl's creation fits in well

with the historical development of the comic strip in America as

it changed during the 1920's and 1930's from broad slapstick to

the family funnies and later the adventure comic strip. The

antics of Ola and Per suggest the "fall guy/straight guy" of gag

and slapstick humor, as in Bud Fisher's Mutt and Jeff.

Then the family situation in the comics expanded between World

War I and the Depression. As Sidney Smith's The Gumps and

Frank King's Gasoline Alley showed the growth of a

typical urban American family, Han Ola og han Per

depicted the Norwegian-American immigrant family in its rural

setting. Other influences appear in the antics of the

American-German twins, Hans and Fritz, in Rudolph Dirks' The

Katzenjammer Kids, and in the marital escapades of Maggie

and Jiggs in George McManus' Bringing Up Father. Then

beginning in 1922 adventures dominated Han Ola og han Per

as Ola and Per took trips to Africa, Siberia, the North Pole,

and tropical islands. This change is parallel to the change that

came to comic strips with the adventures of Roy Crane's Wash

Tubbs in 1924, George Storm's Phil Hardy and Bobby

Thatcher in 1925-27, and Harold Gray's Little Orphan

Annie of 1924 which introduced exotic adventures with

homespun right-wing ideas.

[7]

Also,

Han Ola og han Per followed the custom of

the early comic books which appeared as reprint collections of

favorite comic strips. Beginning in 1921, Rosendahl's comic

strips were reprinted in eight volumes which were intended as

"come on" premiums for subscribers to the Decorah-Posten.

The family nature of the first

years of Han Ola og han Per is in keeping with the

tradition of Norwegian-American immigrant literature to depict

the immigrant in relation to his family -- for the main motive

for the Norwegian immigrant was a better life not just for

himself but for his whole family. The cast of characters for the

Ola and Per comics includes their relatives. The six main

characters are Ola, Per, Lars (Per's brother), Polla (Per's

wife), Værmor (Per's mother-in-law), and Dada (the child of Per

and Polla). Most of the strips focus on Ola and Per but

frequently a series features one of the other characters, and

sometimes the characters play supporting roles or serve as foils

to Ola and Per. Several times Ola's wife, Mari, enters, but she

is usually said to be on her way to Minneapolis or Norway. Each

of these characters is delightful mainly because each embodies

incongruous traits and contradictions.

With Ola and Per as the center, the

strips show two neighbors who go through an endless variety of

experiences with one or the other coming up with some fantastic

new idea. As the center of his family, Per is possibly the main

protagonist. He is drawn as the tall, long-legged, full-bearded

character who always wears his Prince Albert coat tails and his

derby hat. In spite of his cultured appearance, he usually has a

tool in his hand. His genius is coming up with new patents that

make the farm family more dependent upon mechanical devices,

possibly thereby reflecting Rosendahl's own interest in new

inventions and certainly doing for rural life what George

Derby's and Rube Goldberg's inventions did for the urbanite.

These patents, however, serve mainly to complicate daily living,

and their use results in chaos. But Per is no more successful as

a Casanova. Once married to Polla and the father of Dada, he

then assumes the role of head of the house who has the authority

to make decisions, even though some of those decisions are

forced on him by others. As the authority on inventions as well

as family, Per plays the braggart or alazon role.

Ola is the good neighbor-farmer who

offers friendly, free advice or seeks a solution from "Mr.

Know-How" to one of his problems. Ola is the eiron

character who remains quiet until his advice is needed or he

needs assistance. Always bare-headed, he is short of stature,

usually wears farmer's overalls, and often appears with his

pitch-fork over his shoulder. Some of his main problems of

coping appear to be caused by his lack of mechanical aptitude or

at least unfamiliarity with operating mechanical devices. His

consultations with Per often result in chaos, however, so that

usually Per is the victim and Ola gets the last laugh, but

sometimes Ola becomes a victim or they both are.

The main representative of the

newcomer to America is Per's brother, Lars, who has been

"educated" at both Oslo and Berlin. His role is clearly that of

the "learned fool." His first reaction when he arrives on the

scene from Norway is shock at the speed here. From then on, Lars

is bounced from one shock to the next as he becomes involved in

the most weird situations imaginable. He is often given tasks

for which he says he knows "exactly what to do," but since he

goes ahead without knowing anything about the chore, the

situation can only end in disruption. His distinguished

appearance -- he has an exceptionally long, narrow beard and

always wears his black top coat with matching stovepipe hat --

hides his naiveté and lack of common sense. When he cannot cope

with rural America any longer, the wise fool decides to go to

China because he has heard that there one man could have several

wives. En route he writes Per from Hollywood saying that he has

accepted a post as a missionary there because he feels he can

use his seven years of religious training to help so many

"ungodly attractive" girls. His religious work ends quickly,

however, probably because he has a constant craving for

"home-brew." Seldom separated from his jug, Lars often shows the

effects of inebriation. When he returns from New York, where he

studied to be a chiropractor, he is soaked in more than

learning. Whether "sacked out" under the haystack or "shined-up"

to the point of sleeping with the pigs, he remains an

entertaining outrage, the newcomer who is the object of

ridicule.

Polla, Per's wife, is a plump city

girl from Fargo, North Dakota, who knows nothing about rural

life. She thinks Fargo is the center of culture because of the

many dishwashing machines, wireless radios, and sleeping porches

there. Although the circumstances of their meeting are not

given, Per brings Polla home from Fargo one spring when he had

gone there instead of plowing as his neighbor had. One week

later when he returns with his "pie fæs," his friend Ola is

flabbergasted. But marriage between the city girl and the

country boy is not always strawberries and cream. Speaking

English more than the others, Polla misses the city and finds

rural life difficult; Per's ineptness does not make him an ideal

husband either. Every now and then they leave each other, but

they cannot stand to be separated and then reunite.

Polla and Per's problems are not

helped by the arrival of Værmor, Polla's mother from Fargo (21

November 1924). She not only represents the stereotyped

mother-in-law, but she also is the hardworking pioneer woman.

Tough, like Mammy Yokum in Li 'l Abner, she finds no task

too great, and nothing fazes her as far as work is concerned.

Moreover, she cannot stand to see anyone loafing when there are

farm chores to be done. But although she and Lars are unlike in

their attitude toward work, they bear a startling resemblance in

appearance. Neither is nature's prize. As Lars describes her,

Værmor's "cheeks are pale . . ., her lips so red . . ., and her

nose is like a rake handle". Yet as soon as she arrives on the

farm, she and Lars fall so in love that neither of them can

work. After marriage, Lars still has his Lizzies of earlier days

write to him. Once when he takes off for Canada to give lectures

on birth control, he says, he has Værmor immediately on his

neck. Through all their adventures, however, and even with

Værmor's constant sniffing out the "moonshine," she and Lars

always end up together. On one adventure when Værmor is carried

off by a gorilla, she is rescued by none other than Lars.

Dada, the youngest of the

characters and the only child of Per and Polla, completes the

family. She shows her precocious inheritance as a baby for when

she is left in the bureau drawer, she calls "Dada". These

amusing characters have become so familiar to many

Norwegian-American families that they literally count Ola and

Per as family members. They display enlarged drawings of them in

living room photo galleries or even paint resemblances on

kitchen match boxes.

Another aspect of the humor is the

slapstick situation in which these unforgettable characters

frequently find themselves. They are caught in a situation which

can end in only one pattern -- violence -- but Norwegians

miraculously survive. Somebody smashes the Ford, the mule

smashes the person, or one character wallops another, but they

come out of the catastrophe alive. There is no end to the

ingenuity displayed in the creation of incidents. Per's gadgets

shatter in bits and pieces; Ola's home remedies, such as washing

hair in gasoline, bring disaster; and airplanes crash land, but

there is never any bloodshed or fatal illness. Even when

dynamite is used, and it often is, the situation explodes, but

the characters involved are not hurt in the least, although they

take a speedy space trip. The technique of exaggeration is used

to blow up the situation to its wildest proportions yet still

retain a relationship between the original situation and the

exaggeration.

The literary artistry of

Han Ola

og han Per is evident not only in the characterization and

situations but also in the imagery. The figures of speech, which

are not overwhelming in number, are appropriately earthy and

homely comparisons to farm life or the natural environment. Per

gets wet as a herring, Lars sleeps like a pig and looks like a

pighouse, the rain comes down like a waterfall, and Værmor's

brow is like snow drifts. Some of the verbal play includes puns

on Lars' being "soaked" -- with learning and liquor, Per's being

saved by a bad "bumper" of the car, Per's being "finished" --

but unable to function, the battle of "Bull Run" coming in a new

edition, and Per's asking, after the bus has gone off the road,

"Is this Decorah?" only to hear, "No, it's an accident". Many

proverbs are repeated in the titles, such as "The one who laughs

last often laughs best", "Haste makes waste", and "One should

not believe everything one hears".

From the standpoint of graphic

artistry the cartoonist uses many of the usual comic conventions

in a realistic, plain, rather crude style of drawing. The speech

balloons are squared off in a box-like manner; hats rise from

the heads to indicate surprise; sleep and snores are marked by

the usual zzzzZZZZZ. One of the most interesting features is the

close continuity of appearance and line from panel to panel and

also from one strip to another. For example, when Lars loses

part of his beard, the next series pictures him as partly

beardless, but his beard slowly grows longer. When Værmor loses

her hair, the next strips show her wearing a turban. The usual

circles to indicate motions of characters are combined

effectively with line continuity in many strips. Generally done

in an understated style, the drawings nevertheless usually end

with a climactic explosion of lines going in all directions. One

of the most effective of all the drawings, however, is the

depiction of back-seat driving which after a confusion of

circles and balloons ends in a blank.

Beyond the literary and graphic

artistry, the historical value of the comic strip lies in its

revelation of the way the Norwegian-American immigrant community

thought and lived. Despite the comic distortions and the

incongruities between the realism of the setting and characters

and the fantastic actions and situations depicted, the humor

vividly portrays common men and their daily lives. In the

depiction of folklife several themes are developed: 1) the pains

and tensions for the immigrant who wants to retain his ethnic

identity at the same time that he is adjusting to American life

with its constant changes; 2) the disruptive effect of gadgets

and machines and the absurd pretentiousness of automated life;

3) the confusion of the human condition, or the world as

nonsensical; and 4) the demonstration that the human being

endures even though he is foolish, weak, and undignified.

The main humorous theme is

certainly the tension between the dream and the real worlds of

the immigrant. Throughout the seventeen-year life of the comic

strip the characters never forget their Norwegian roots, nor do

they give up their language in spite of their initial problems

in social matters because they misunderstand American speech or

signs. For example, when Per complains that he never has a

chance with the young girls, Ola advises him that the problem is

simply that he cannot speak "Yeinki." Following Ola's advice the

next time he meets a young girl, he lifts his hat and greets

her, "Hello, Pie Fæs." Per lands in the gutter where he comforts

himself with the favorite sentimental song of Norwegians in

America, "Kan du glemme gamle Norge?" ["Can You Forget Old

Norway?"]. Initially baffled by the speed at which all the

vehicles move in America, the newcomer Lars falls off on his

first motorcycle ride. Soon after, he tries to keep up with

cars, tractors, and airplanes and keep away from salesmen and

sheriffs. But the adjustments made by the city girl who goes to

the farm are just as difficult, as Polla discovers.

The educated newcomer experiences

the most problems in coming to the farm, however. Struggling

with new customs, Lars' attempt to put the crupper on Kate ends

in his being kicked out of the barn. Nor can he drive the team,

feed the calves, manage the mules, or cope with snakes. When he

cooks soup, he uses meat from the skunk, and finally when he

tries to spray poison on the potato bugs, he admits he prefers

beautiful old Norway. "It is not easy to be a newcomer," he

says. Even after Per and Ola are sure Lars is learning, he shows

his ignorance of tilling the soil when he interprets the

direction to follow the cow literally. When Lars finds his

consolation in "moonshine," he reveals his attachment for the

old country by singing "Ja, vi elsker dette landet," the

Norwegian national anthem, but often the effects of moonshine

take him beyond chauvinistic consciousness. Eventually his

ineptness leads only to a series of frustrated attempts at

working not only as a farmer but also as a chiropractor, a

missionary, a radio announcer, an artist, and a reducing

specialist. His work efforts bring rags, not riches, so that

finally his family threatens to put him in the poor house.

Driven to near-madness by Værmor's domination, he ends up

standing on top of the chimney and throwing bricks down on the

people. His experiences bring him closer to insanity than

success in a reversal of the "American Dream" theme which was

also satirized by Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and other

critics.

Among the reasons for the

immigrant's survival, however, are his willingness to attempt

the impossible in spite of the odds and his insistence on

retaining customs from the old country. In carrying out the

impossible, Per and Ola each reveal themselves to be among the

"natural born fools," such as Sut Lovingood created by George

Washington Harris of the Southwestern humor tradition. The

fools' actions bring punishment to themselves, and sometimes

these foolish endowments help to reveal the hypocrisy of

supposedly respectable members of society and then to punish

them appropriately. When trying to control the cattle, Per's

"natural born" characteristics get the better of him and he

tries to stop the cattle from sneaking back into the barn and

into another cow's stall. As often happens, the wrong object or

person becomes the victim of a violent accident. Usually,

however, the fool becomes the victim of his own "know-how," as

when Per attempts to start the manure spreader. Only too often

Per is laughed at by the people he tries to help, but sometimes

they become the targets of ridicule. His most common means of

coping with his world and realizing his dream is to come up with

some complicated gadget. One example of this is his "sow

force-feeder" which he plans to use so that the three pigs he

will ship to market weigh 1500 pounds, thereby bringing him many

thousand dollars. He is confident of his success because "it is

a business which has never blown up, so to speak" until his pig

explodes. Another invention of the mechanically inclined Per is

his perpetual motor. This time the "educated fool" is helped by

the practical Ola, who cranks the motor so that the machine

runs.

When members of mainstream society

interfere with Per's, Ola's or Lars' likes, the Norwegians are

not silent or inactive. The main victims of Per's dislike are

book agents, unless they are girls. Also subject to ridicule are

dentists, chiropractors, the sheriff, the local bureaucrats who

administer farm relief and the politicians in Washington who

passed a wife-exchange law which Lars took advantage of to

exchange Værmor for a peanut roaster. The hard-working pioneer

woman who ends up as boss in the house, as Værmor often does, is

the target of much satire. The worst Værmor receives for spying

to see if Lars has moonshine is a manure pie in her face, but

other objects come her way as well. Actually there is always a

type of justice meted out, as the immigrants disliked anyone who

posed as high and mighty. There is a devastating attack on

mankind in general when human beings are depicted as having

non-human or animal qualities, especially when Per mistreats

animals, and when Lars makes love to Værmor, praising her animal

features at such length that he "falls in weakness and lies like

a swine", as he also does when he over-indulges in his jug.

These attempts to expose that which was not what it seemed to be

were further manifestations of the basic desire for regularity

and congruity in life. Deviations from a rational, purposeful

creation are ridiculed. The comic strips also suggest that in

pioneer times people had to cope by many means -- not the least

of which were physical pranks, such as the upsetting of

love-making by bringing in a cow. Any attacks on persons in

authority reflected the basic attitude, but questionable logic,

that "everybody is as good as everyone else -- and a bit

better."

Retaining ties with the folk

culture and customs of Norway also contributes to the humorous

situations of the immigrant. A typical Norwegian, Værmor must

take time to have a little "kaffi-skvet," a wee drop of coffee,

before she leaves the house even though the flood is coming with

full force. On another occasion coffee revives Værmor when all

other remedies fail, just as whiskey does for Lars. When Ola and

Per are stranded in the North Dakota blizzard, whose skis do

they find to save their lives but the ones they attribute to Per

Hansa in Rølvaag's Giants in the Earth. When Lars downs

rat poison, he shows the effect on him by vigorously dancing the

Halling hat dance. Other evidences of Norwegian folk culture are

found in telling numbskull stories, in blaming ghosts for the

appearance of strange creatures, in recalling troll mischief,

and in singing traditional Norwegian songs, such as the national

anthem, "Yes, We Love This Land of Ours", the nostalgic "Can You

Forget Old Norway?", and "How Glorious is my Land of Birth". The

traditional habit of the Norwegian's finding the chief

nourishment in "graut" or porridge is a theme of the strip from

the first issues to the last. If the porridge has not been made

with cream from the cow that has just calved, the quality is

inferior and not suitable, according to Ola's wife. Talking with

his wife about her Ford, Ola quotes from Ibsen's Peer Gynt.

"You can tell the big shots by their mounts," referring to Peer

Gynt's riding into the Dovre mountains with the Greenclad Woman

on a huge pig. Also ridiculed is the habit of joining fraternal

organizations, such as the Sons of Norway, just for the sake of

belonging to an "old outfit" of people from the Old Country. The

best satire is on the currently popular search for ancestral

roots, for when Ola and Per haul out the books to find out where

the family stems from in Norway, Per points to the picture of

grandpa -- a gorilla.

Some of the best humor concerning

the immigrant experience comes in a delightful parody of the

adventure motive for immigration. The immigrants coming home

from Siberia aboard the "Spirit of Decorah" land on an

island where they undergo a series of fantastic encounters.

After frightening meetings with snakes and gorillas, they decide

to build their "castle in the sky" only to lay the foundation on

stones which prove to be large turtles that wake up and walk

away, wrecking the house. One of the first visitors to the

island is Smart Aleck, an agent selling the "Sure Grip Automatic

Monkey Wrench." When Per discovers the "artocarpus flapjackus"

or pancake tree, he overeats to the point where he thinks he is

dying, so he wills his hat to the Decorah Museum, the main

Norwegian-American immigrant museum. After having difficulties

in crossing a river, the immigrants are threatened by volcanic

eruption, from which they take shelter in a bat-filled cave.

After meeting a dinosaur, they tangle with a monkey who steals

Lars' clothes. Værmor cries because Lars has to go naked, but he

says that is nothing to get excited over. The New World Adam has

an extra suit of clothes in the airplane. Eventually the group

finds a home in a huge stove pipe, and then Værmor builds a raft

to carry them back to civilization. But "things look dark for

the pioneers." After several unsuccessful attempts to return to

America, they finally arrive. They know they are home because

Ola sees a vehicle marked "bus," but Per comments, "It says

'booze' on it so we are in the U.S.A." This delightful series of

adventures ends with Ola and Per's appreciation speech upon

being back in America. This is interrupted by Polla's

announcement that down by the haystack there is a sleeping tramp

-- Lars with his jug.

The adventures of immigrants are

mocked frequently in other trips: a North Pole trip where the

immigrants find Amundsen's plane and Andrée's balloon; a trip to

North Dakota during which, after being buried by a blizzard,

they set up a shopping center with Per and Ola's runabout 5 and

10 cents store, Polla's lunch counter, Værmor's "bjuti" shop,

and Dr. Lars' "redoosing" specialist's salon; and an attempted

visit to the Chicago World's Fair which ends with a robbery that

eventually brings Ola and Per a large monetary reward for their

return of the gold. These Gilligan's Island adventure series are

not only directly related to immigration humor but they parallel

the changes noted in comic strips of the late 1920's and 1930's

from family funnies to adventure series.

[8]

The other themes, already mentioned

briefly in the main theme of immigrant adjustment, are developed

quite extensively throughout the comic strip. Per's perpetual

invention of a complex mechanism that wears itself out and

everyone connected with trying to make it work appears

throughout the entire series. Whenever Per encounters a little

commonplace problem whether in the house, the barn, or the

field, he attempts to "solve" it by inventing a fanciful

machine. For the house he created the dirty clothes chute, a

dishwashing machine, a hoist for bringing dishes to the table, a

Hoover Commission kitchen-floor cleaning device, a gimmick for

emptying the dish water, the "lazy man's jump bed" and an

electric comb. Of course, part of the irony of the humor is that

many of these gimmicks anticipated real technological

developments.

The endless contraptions for the

farm work included a knock-out grub machine, a staple puller, a

weather balloon, an electric fan to drive the windmill, an

egg-cleaning machine, a wood-cutting machine, an electric pig

fence, an air-pull cultivator, a cyclone chicken house cleaner,

a self-cleaning cow barn, a rotary hog feeder, an air-push hog

loader, a haystack loader, a whirl-wind steam chopper, a Model

34 Farm Bjuro [dresser] operated by compressed air, an iron cow,

a tip-over, quick-oiling windmill, a high-speed manure spreader

and even a shock-absorbing wall. A lightning postpuller

illustrates how these inventions symbolized man's ability to

expend maximum effort to create a machine to achieve what can be

done more simply by hand, for Per and Ola spend more time

getting the gadget in working order than Lars does in completing

the task with the spade. But with the machine the person becomes

a working part, usually the one who botches the mechanism. These

inventions remind us that the automated life is not everything

it is supposed to be. Far more rigid than man, the contraptions

suggest that human values can survive in the New World only as

long as man is flexible and able to laugh at his own creations.

As Walter Winchell quipped about Rube Goldberg's works,

"Generations of Americans have roared with laughter at Rube

Goldberg's machines -- but the combined scientists of the world

cannot and never will -- produce a machine which laughs at a

man."

[9] For this, Rosendahl's Brave New World offered no

possibilities either.

The Norwegian's gadgets were used

to control people, too, such as the device to get rid of book

agents, the safety pedestrian catcher, and the gimmick Lars used

to seed from an airplane. The changing world of machines is also

evident in the vehicles -- from the motorcycle to the Ford, to

the airplane, and finally to a "new grasshopper" that looks like

the helicopter. Other inventions which the immigrants learn to

use are the telephone, the wireless, and the Victrola. The basic

point behind all of these strips seems to be that in spite of

technological advances human beings never really change.

Although man may expand his control of his environment or

enlarge its sphere by coming to a new land, he does not change

radically either his character or the meaning of life. But life

changes, and people have to adjust -- or be destroyed by

violence. Progress is really an illusion. We human beings delude

ourselves into "thinking that we're pushing ahead, but when we

stop we're at the start."

[10]

But if human beings don't change,

the one certain result of their simply being alive is confusion.

Much of the humor of the immigrants is the result of the

characters' merely trying to adjust to the inevitable changes of

daily life brought on because people choose different clothes

styles, need cures for disease or weakness, fall in love and

marry, struggle with daily tasks, and even spend a few hours in

recreation. In Han Ola og han Per, Værmor throws away her

out-dated knickers; Lars' clothes shred into rags; Værmor tries

Dr. Lars' home hair treatments; Værmor and Lars find their

courting interrupted by bees, wasps, and cows; Per and Ola use

nitroglycerin to blow the skins off baked potatoes; and the

whole group barely survives playing checkers and listening to

the radio. Often these simple activities explode into fiery

violence, sometimes caused by the use of dynamite. These fumbles

and falls dramatize the limitations of all human beings and

suggest that chaos is the basic human situation.

The final theme then is that in the

humorous struggles of the human being as he bridges two worlds

-- both the geographical one of the Old and New Worlds and the

technological one of the mechanically complicated versus the

simple -- the individual endures. Certainly Ola and Per grow to

mythic proportions, for despite their hardships and

catastrophes, they end their existence by going off on a trip to

Norway. They take in stride the daily frustrations and problems,

and despite constant disaster, they continue to work to improve

their lot. Værmor, too, is put to the greatest test not only by

her family but also by social enemies, yet she wins by foiling

robbers and even helping Lars to regain his self direction. Lars

is the one who comes closest to succumbing to the insanity of

life in the New World, yet in the last strip he is running to

catch the plane.

The humor of Rosendahl's

Han Ola

og han Per is valuable for history and literary art. As

history it depicts the tension between the immigrant's vision of

the Promised Land and his actual encounters with the New World

with its increasing reliance on technology to complicate even

the most simple human process. As literature it offers vivid

characters who survive the chaos of everyday living as well as

the violence of fantastic adventures. Best of all, Rosendahl's

comic strip offers these riches with amusement. Han Ola og

han Per deserves a special place not only in

Norwegian-American immigrant culture but in American and

Norwegian culture at large.

Notes:

-

Han Ola og han Per is

currently reprinted in The Western Viking, published in

Seattle, Washington, and in several Minnesota newspapers such as

The Valley Journal and The Starbuck Times.

-

Each of the 599 comic strips of

Han Ola og han Per is identified by parenthetical reference

to the number of the comic strip in the "Order of Publication."

This list of comic strips arranges them by date of issue in the

Decorah-Posten, but adds the Rosendahl number, the volume

number of the collected edition in which the comic strip was

reprinted by Anundsen Publishing Co., Decorah, Iowa, and the

page of the strip which was assigned by numbering consecutively

within the volume.

-

Odd S. Lovoll,

"Decorah-Posten:

The Story of an Immigrant Newspaper," in Norwegian-American

Studies and Records, 27 (1977), 77 and 96.

-

N. W. Ayer & Son's American

Newspaper Annual and Directory (Philadelphia, 1920), p. 291;

1935, p. 287; 1950, p. 323; and 1972, p. 343. The circulation of

Decorah-Posten numbered 29,545 in 1935 and 5,867 in 1972.

-

Interview, Frederick Rosendahl,

Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 10, 1981.

-

Decorah-Posten, 8 January

1926, p. 5. Printed in translation p. 5.

-

Jerry Robinson,

The Comics: An

Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art (New York: Berkley

Publishing Corporation, 1976), pp. 57, 71, 88.

-

Stephen Becker,

Comic Art in

America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959), p. 86.

-

Peter C. Marzio,

Rube Goldberg:

His Life and Work (New York: Harper and Row Publishers,

1973), p. 197.

-

Marzio, p. 175.

Published on "The Promise of

America" website

http://nabo.nb.no/trip?_b=EMITEKST&urn="URN:NBN:no-nb_emidata_1302"

|

Author: |

Buckley, Joan N. |

|

Title: |

The

Humor of Han Ola og Han

Per |

|

Host document: |

Han Ola og

Han Per

Author: Rosendahl, Peter J. |

|

Printed: |

Oslo 1984 |

|

Published: |

1984 |

|

Owner: |

Nasjonalbiblioteket, avdeling

Oslo - Norsk-am. saml. |

|

![]()